One of the most central (and at the same time controversial) issues pervading our attempts to reconstruct the proper way to play the baroque violin is quite simply this: “how are we supposed to hold the baroque violin? ” Briefly stated, there are two relatively sharply divided schools of thought - the one, “chin off", following iconographic evidence and the clear statements of writers like Geminiani (1752): “The violin must be rested just below the Collar-bone", and the other, “chin on", following the gospel according to Prinner (1677), and later Leopold Mozart (1756) , both of whom say (put briefly), hold the violin firmly with your chin, or you can't play properly. As we shall soon see, there is clear historical evidence for both positions, and I think a very good starting point in our enquiry here is to come from the evidence, and absolutely to avoid any dogma. In fact, one of my main aims in this (and all my other Essays), is precisely to defuse any sense of absolute doctrine - we are in no position today to build any such edifice on the flimsy evidence which has come down to us. Let us proceed with humility and an open mind.

Before looking in detail at the evidence and its implications, perhaps a few words about quite why it's so important, aside from historical fidelity. If you rest your violin somehow, somewhere on your collar-bone, chest, whatever, rather than holding it firmly between shoulder and chin, then, quite apart from the ensuing physical freedom (if you can avoid the tension resulting from fear of dropping the instrument!), the entire sound world automatically changes - the default bow stroke is now soft edged and articulate and a continuous wide vibrato becomes more or less impossible.1

Suddenly two of the distinguishing features of baroque performance practice become almost a priori - namely a “shaped” sound, and the use of vibrato as an ornament rather then part of tone production. In many ways, then, the chin-off position is an excellent first step in the attempt to discover a new (or do I mean “old”) sound-world/aesthetic. But of course, it's not that simple, because these advantages have concomitant disadvantages; - not only does shifting become a major issue, but the violin has a tendency to wobble, making string crossing somewhat precarious, and the necessity of supporting the violin with the left hand jeopardises intonation.2

So the HIP (Historically Informed Performance) world has polarised; - the chin-off folk claiming that chin-on violinists are compromising authenticity for convenience and that they don't make a proper baroque sound, while the chin-on supporters in turn claim that if you don't support your violin with your chin, you can't shift properly, you play out of tune, and you make a thin sound. Moreover, if you do decide to play chin-on but “historically”, that is, without shoulder rest and chin rest, you have to deal (depending on your physique) with how to get your chin close enough to the violin to support it.

In fact, our opening question as posed - “How are we supposed to hold the baroque violin?” - is too simplistic. We are looking at over one and a half centuries - if we define the baroque period as extending from 1600 to around 1761 (the date of our “last” source, that of L'Abbé le fils). During this time the violin, its music and its technique developed beyond recognition. And are we talking about the violin in France, Italy, Germany or England? In church, court or tavern? It is clear that any evidence we find and any answers we propose need to be carefully considered with respect to time, place and context. And further, the purpose and “reliability” of the source must be verified - are we dealing with, for example, a treatise written for professionals or amateurs, by an eminent violinist, or something cobbled together by a publisher. For those who have read enough and want to get on with the business of playing the violin, a practical answer to the question as posed might be: “in its early days, the violin was held low on the chest (or even resting on the belly), and during the period, as music became more technically demanding and shifting became ever more prevalent, so the violin crept ever higher, and the chin started to be used to support the instrument.” So if you're going to play Cima or Castello, you can (some would claim should) play chin-off. But if you're going to play Locatelli, then (pace Geminiani) perhaps you'd better put your chin on! But if the issue were this simple, there would probably be no controversy, just the awkward decision about whether (being 21st century performers who play 150 years or more music) we should learn various different ways of playing, or whether we should decide on one technique, and compromise. The thing is, that there IS evidence that even in the middle of the 18th-century, chin-off performance was, if not prevalent, at least used by some. And it is also clear that there was no “accepted” norm, and that many different techniques existed side by side both in time and place So, what is the evidence? Let's start with the written material ... I've listed here the treatise author, place, date and short relevant phrase [for the quote in context, and discussion of each source, see Part II].- Jambe de Fer (Lyons, 1556) “ ...it is supported by the arm”

- Praetorius (Wolfenbüttel, 1614/20) “...it is held on the arm”

- Prinner (Salzburg, 1677) “... the violin must be held firmly with the chin”

- Falck (Nürnberg, 1688) “Place the violin below the left breast, the instrument should lean a little downward towards the right.”

- Merck (Augsburg, 1695) “One should hold the violin nicely straight under the left breast, leaving the arm free, not resting against the body/belly”

- Speer (Ulm, 1697) “The remainder, how one holds the violin correctly in the hand, rests it on the breast, leads the bow ... that a trusted teacher must show his student”

- Playford (London, 1667)“... the lower part of the violin must be rested on the left breast a little below the shoulder”

- Matteis, according to Roger North 1670's “... rested his instrument against his short ribbs”

- Lenton (London,1693) “... as I would have none get the habit of holding an Instrument under the Chin, so I would have them avoid placing it as low as the Girdle”

- Monteclair (Paris, 1711/12) “To hold the violin securely, the tail-piece is placed against the neck just under the left cheek.”

- Corette (Paris, 1738) “... he must place his chin on the violin”

- Crome (London, 1740) “let the back part rest on your left Breast. The best way is to stay it with your Chin”

- Francesco Geminiani (London, 1751) “The violin must be rested just below the Collar-bone, turning the right-hand Side of the Violin a little downwards”

- Leopold Mozart (Augsburg, 1756) “The violin is placed against the neck so that it lies somewhat in front of the shoulder and the side on which the e-string lies comes under the chin, whereby the violin remains unmoved in its place even during the strongest movements of the ascending and descending hand.”

- Herrando (Paris 1756) “The tailpiece must come under the chin, being held by it there, turning the head slightly to the right.”

- L'Abbé le fils (Paris, 1761) “The violin should be placed on the collar-bone in such a way that the chin rests on the side of the fourth string”

A brief perusal of the above reveals that, Prinner and Geminiani apart, the progression of the violin from lower (chin-off) to higher (chin-on) is clear. Prinner is exceptional in advocating so early that the chin should be used, whereas Geminiani is exceptional for the exact opposite.

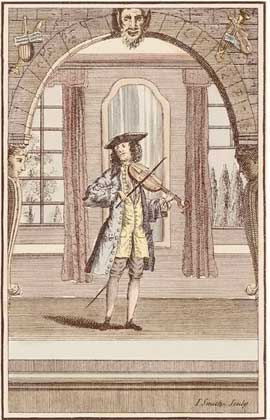

Iconographic evidence reveals a similar move from low to high - although, again, not without exception. The portrait of Veracini, which appears as the frontispiece to his Sonate Accademiche of 1744 seems to demonstrate both the use of a very long bow, and a distinctly chin-off position.

Orazio Lomi Gentileschi (1563 - 1639) Violin Player c. 1621

Gerrit van Honthurst (1592 - 1656)

The Violin Player, 1626

Judith Leyster (1609 - 1660)

The carousing couple (1630)

Charles André van Loo (1705 - 65)

The Grand Turk giving a concert

Peter Prelleur

The Modern Musick-Master, 1730

Michel Corrette

L'Ecole d'Orphée, 1738

Franceso Maria Veracini

(1744 Sonate Accademiche)

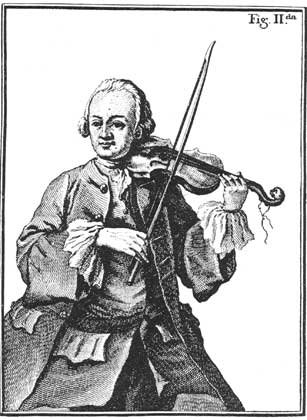

Leopold Mozart 1756

So, there we are, the evidence is in, but it's not clear that we have access to a better answer than that already given above. Other than the obvious (and already mentioned) observation, that a chin-off position is clearly more appropriate for earlier (roughly 17th-century) music, it is difficult to be prescriptive about what today's player should do. What does seem certain is that there was no “established” method. Each violinist came to his/her own solution, most likely depending on the repertoire being played and individual physique. Biber, for example, one of the most renowned virtuosi of the day, wrote music that, in spite of its virtuosity and high position-work, is eminently playable without support of the chin, as he always gives ample opportunity (an open string, for example) to get back down!3 For later music, when shifting becomes more prevalent and the issue becomes more pressing, it is difficult to be more to the point than Leopold Mozart. He notes that the chin-off position (pictured here):

“ ... has a rather pleasant and relaxed appearance. Here the violin is quite unconstrained; held chest high, slanting, and in such a fashion that the strokes of the bow are directed more upwards than horizontal. This position is undoubtedly natural and pleasant to the eyes of the onlooker, but somewhat difficult and inconvenient for the player as, during quick movements of the hand in the high position, the violin has no support and must therefore necessarily fall unless by long practice the advantage of being able to hold it between the thumb and the index-finger has been acquired”

Hence, his recommendation to hold the violin “under the chin”. Moreover, independent of the shifting issue is that of a stable left-hand position - holding the violin between thumb and fingers without the support of the chin necessitates a particularly flexible and ever-changing left hand position, which once again is not easily mastered without “long practice”.

Should we decide rather to take Prinner's and Leopold Mozart's advice and use the chin-on position, there is one very important consideration, which is quite simply not mentioned in any of the 17th or 18th century sources; - namely, how to get the chin close enough to the violin to support it, without the use of some kind of shoulder pad (first mentioned by Baillot in 1834), a chin-rest (invented around 1820 by Spohr), or even more extreme, a shoulder rest (a mid 20th century invention). The two obvious solutions - to raise the shoulder, or turn and tilt the head (or a mixture of the two) - can result in a cramped posture which can in turn have drastic physical consequences in the long term. In this case, pure common-sense and awareness of our own build and ability is essential.

In the end, then, we are each left to our own preferences. Being capable of both positions, and using whichever seems the more appropriate for the repertoire being played might be the most satisfying solution. But that would mean learning two radically different techniques, for both left and right hand. If we opt for employing only one position, then we need to balance on the one hand the “long practice” needed to master the art of holding the violin “between thumb and forefinger”, with the challenge, on the other, of finding a physically flexible and viable way of supporting the violin with the chin.

- 1. Of course, you can play with a long strong legato bow stroke, and you can vibrate continuously, but it requires extra work, and does not seem to arise naturally from such a position. The type of bow-stroke is also quite clearly also a property of the shape of the baroque bow itself, but more of that in another Essay. return to text

- 2. Once again, of course, it is completely possible to overcome these disadvantages; they are most assuredly just that, disadvantages, not impossibilities. My point is merely that the absence of support makes these issues more difficult that otherwise. return to text

- 3. It could well be that Biber is one of the “respected virtuosi” to whom Prinner refers, when he talks about some people resting their violin on their chest. More of this in Part II. return to text